Books Are Machines

Solo show at Bemis Public Library in Littleton, CO

September 26, 2025 - February 14, 2026

What follows is an adapted version of the talk and slide presentation I gave on October 11th, 2025 at the opening reception.

Good afternoon everyone, My name is Maya Buffett-Davis, Welcome to my talk about Books Are Machines.

I want to begin today by thanking a few of the people who made this show possible. I want to thank Zachary Davidson at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art for giving me this opportunity and helping with install. I have so much gratitude for all of the incredible librarians and staff here at Bemis. I also want to thank Lori Emerson and libi rose streigl at the Media Archaeology Lab. Evan Blackstock and Garrett Bryant for all of their fabrication guidance. My ceramics co-hort for helping me in the final push towards finishing this show. Ethan Cherry for his hours of help documenting the Alphabet piece. And Annaliese Cole-Weiss and Cal Young for their epic install help and support all around.

And I want to thank all of you for being here today. It is an absolute honor and dream come true to have a show in a public library and specifically this wonderful library in the vibrant community of Littleton. Libraries are an essential resource that make books and knowledge available to our communities. They are also one of the few places you can go without the expectation of spending money. Similarly art in public spaces, like libraries, is accessible, free and open to engagement for everyone. I appreciate you all coming out today to support public art and libraries.

So, I am going to structure this talk like a seated walk through. I will talk about each piece in the show, I will share about my process and thinking going into the work, and then I’ll give some time for a couple of questions after I talk about each piece. There will be some time at the end for any remaining questions.

To kick it off, The Dewey Machine. The Dewey Machine is an interactive sculpture that prompts people at the library to pick three tiles that correspond to a number in the Dewey Decimal system and thus leads them to a randomly selected book or small group of books in the library.

The Dewey Machine (2025) 90 marbles, ceramic, cherry wood, magnets

In developing this piece, I was thinking a lot about the joy of randomly stumbling upon the perfect book: the feeling of serendipity that comes from encountering a book at a uniquely appropriate moment. These days, the decision of what book to read is often mediated by digital technologies or artificial intelligence. The process of finding a book usually entails knowing what you are looking for and having the technology tell you exactly how and where to get it. The Dewey Machine provides visitors the opportunity to randomly stumble upon a book, and I hope will encourage more wandering in the aisles.

I think a lot about the paralyzing nature of choice and how comforting it is for machines to make decisions for us. It is often the path of least resistance to let the algorithm decide what we eat, wear, look at and read.

The Dewey Machine provides a similar comfort of not having to know exactly what you are looking for. However, unlike the algorithms that control what we are exposed to and mediate our consumption choices, The Dewey Machine does not have a filter bubble. The random nature of the machine will likely lead you to explore topics and books you may have never encountered before. The algorithmic function of The Dewey Machine authentically maintains the possibility of discovery.

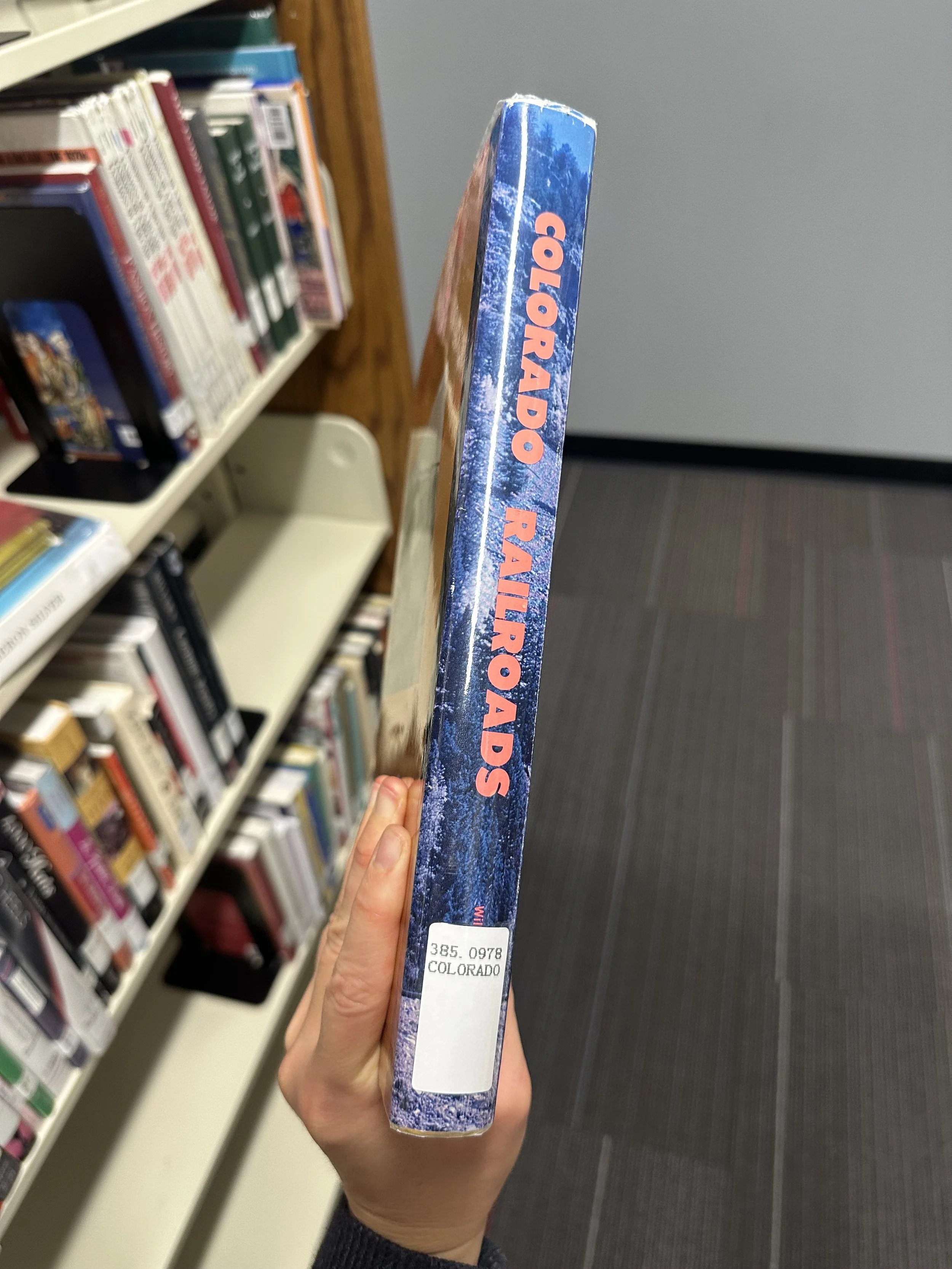

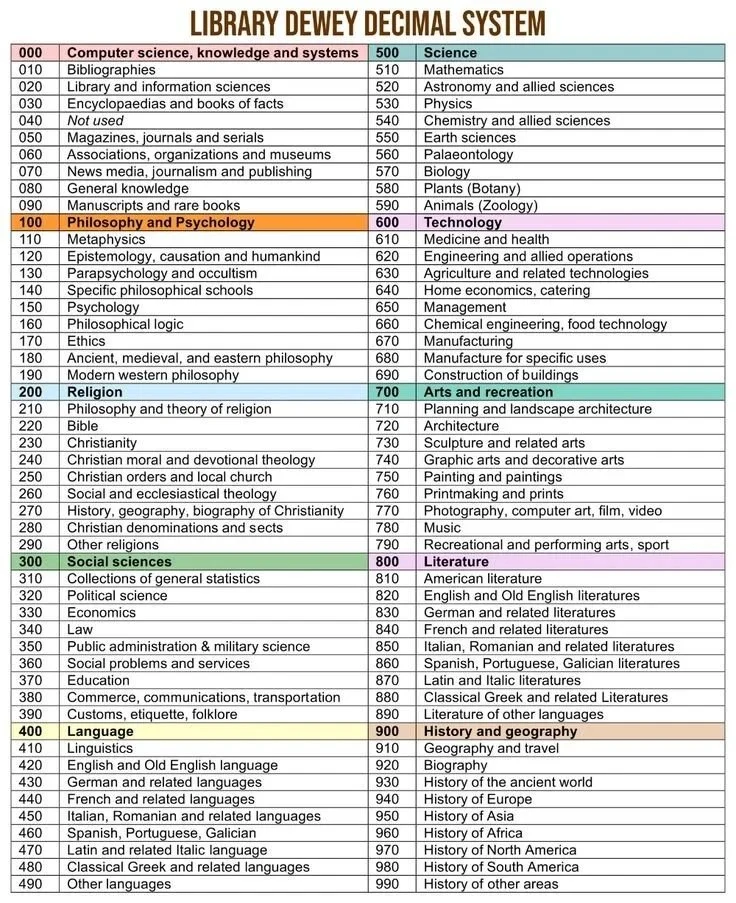

So, a little background on the Dewey Decimal System. The Dewey Decimal system is a library classification system that was created by the librarian, Melville Dewey in 1876. This System organizes books based on their contents, their subjects. The core of a dewey number consists of 3 digits and each of those digits hold information about any given book. Let’s take for example this book on Colorado Railroads from the stacks here at Bemis. 385. The 3 means this book falls under the classification of Social Science, the 8 narrows that to commerce, communications and transportations, and the 5, corresponds specifically to railroad transportation.

So, a bit about the process of making this sculpture in relation to the Dewey Decimal System. The image on the left is of the 90 tiles that make up The Dewey Machine. Each tile, on one side has a marble and on the other side a number. In this picture, each row has tiles numbered 0 through 9 and each row is fired to a different temperature, ranging from roughly about 1400 degrees Fahrenheit to 2000 degrees Fahrenheit.

In theory, The Dewey Machine could function with only 30 tiles. I decided to make 90 tiles to allow for more than one person to interact with the machine simultaneously and to increase the replayability of the machine. The directive to choose three tiles works nicely with how the Dewy Decimal System is structured. Remember, each individual digit in a Dewey Decimal number holds meaning. Let’s say for example I select a tile that has a 7 on the back, that means my book will fall under “Arts and Recreation,” I pick another tile, let’s say it’s a 3, that further specifies books that fall under the “Sculpture and related arts” category, then lets say I pick a final tile that’s a 1, that means I will be selecting from books about sculpture made from clay and similar materials. If The Dewey Machine itself were to be classified in the Dewey Decimal System it would be 731.

Visually, I imagined the melting of the marbles as a nice parallel to the sort of zooming in, and focus on more specific information that happens as you select Dewey Decimal digits.

In the proposal process for this work, the library very reasonably suggested that I might want to design the piece so that the tiles were not fully removable. In the studio, I workshopped different hanging methods that would make it impossible or at least much harder to remove the tiles from the library, I thought about tying the tiles with string or latching them to chains, I didn’t like any of these methods, they made the tiles look like keychains. On top of that, I realized that having the tiles be removable was important to the work. On one level, the removable tiles make sense for the function of the piece, and on another level it sets up a relationship between the person and the machine that necessitates trust and care.

Are there any questions about The Dewey Machine?

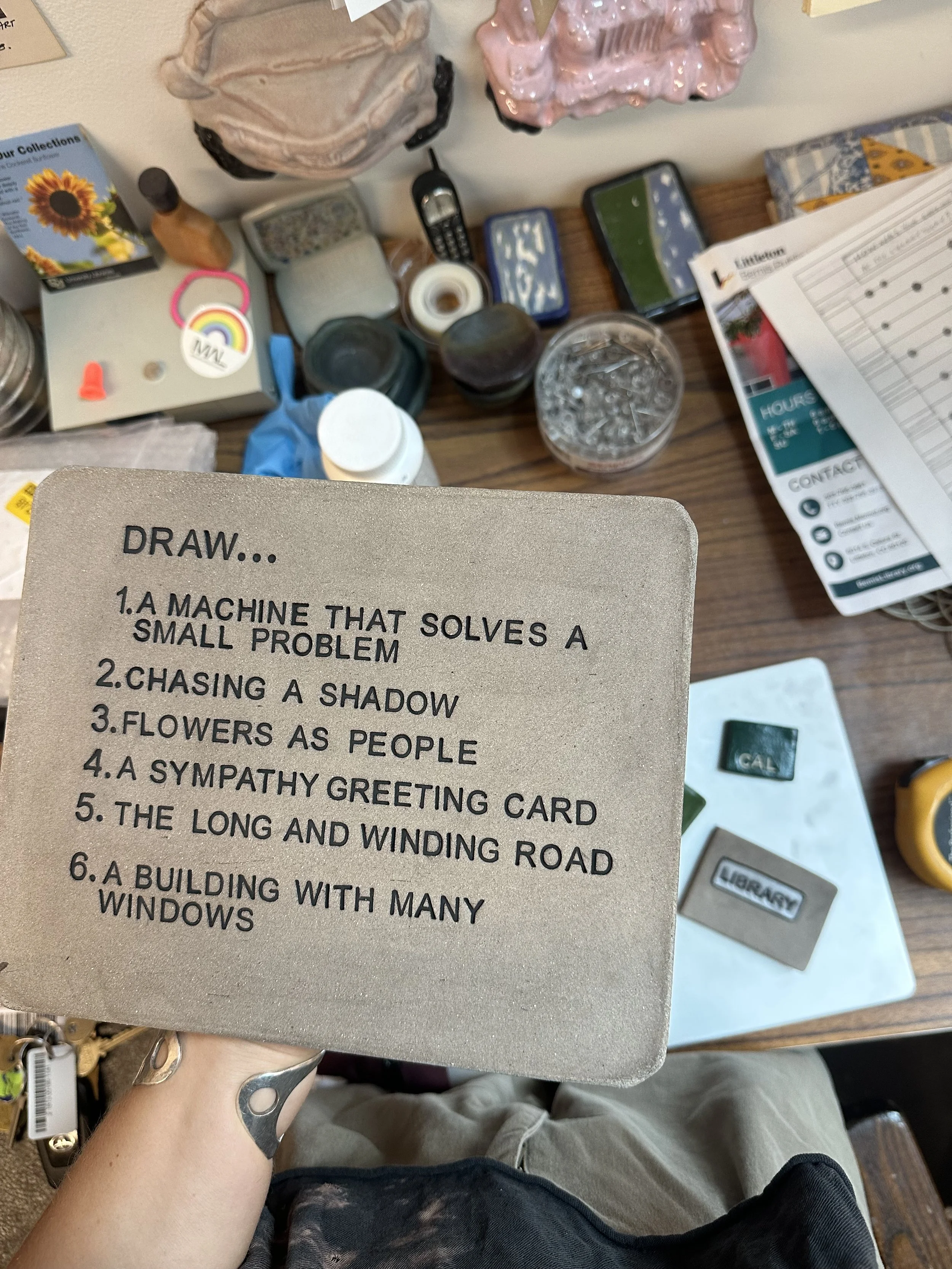

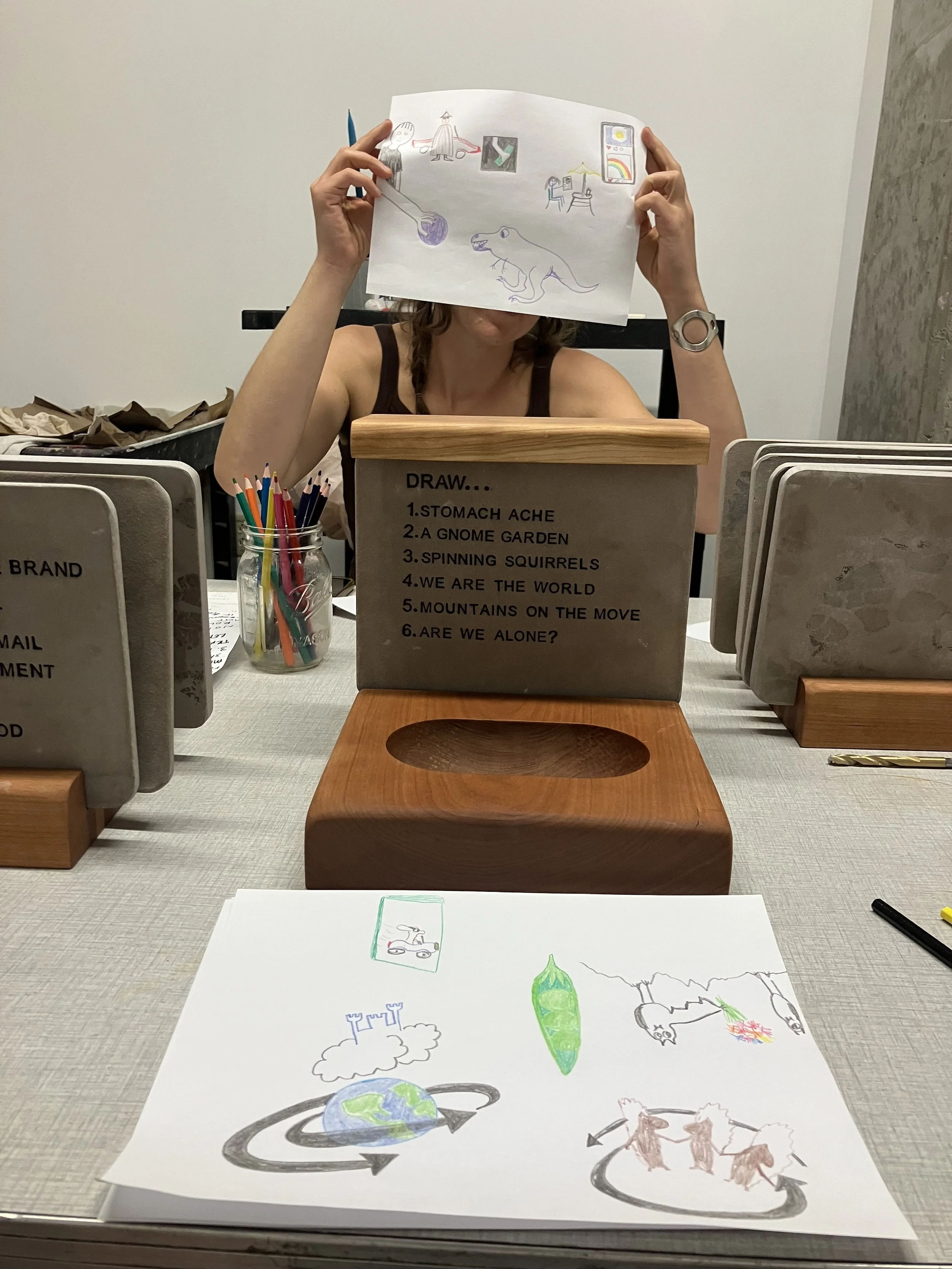

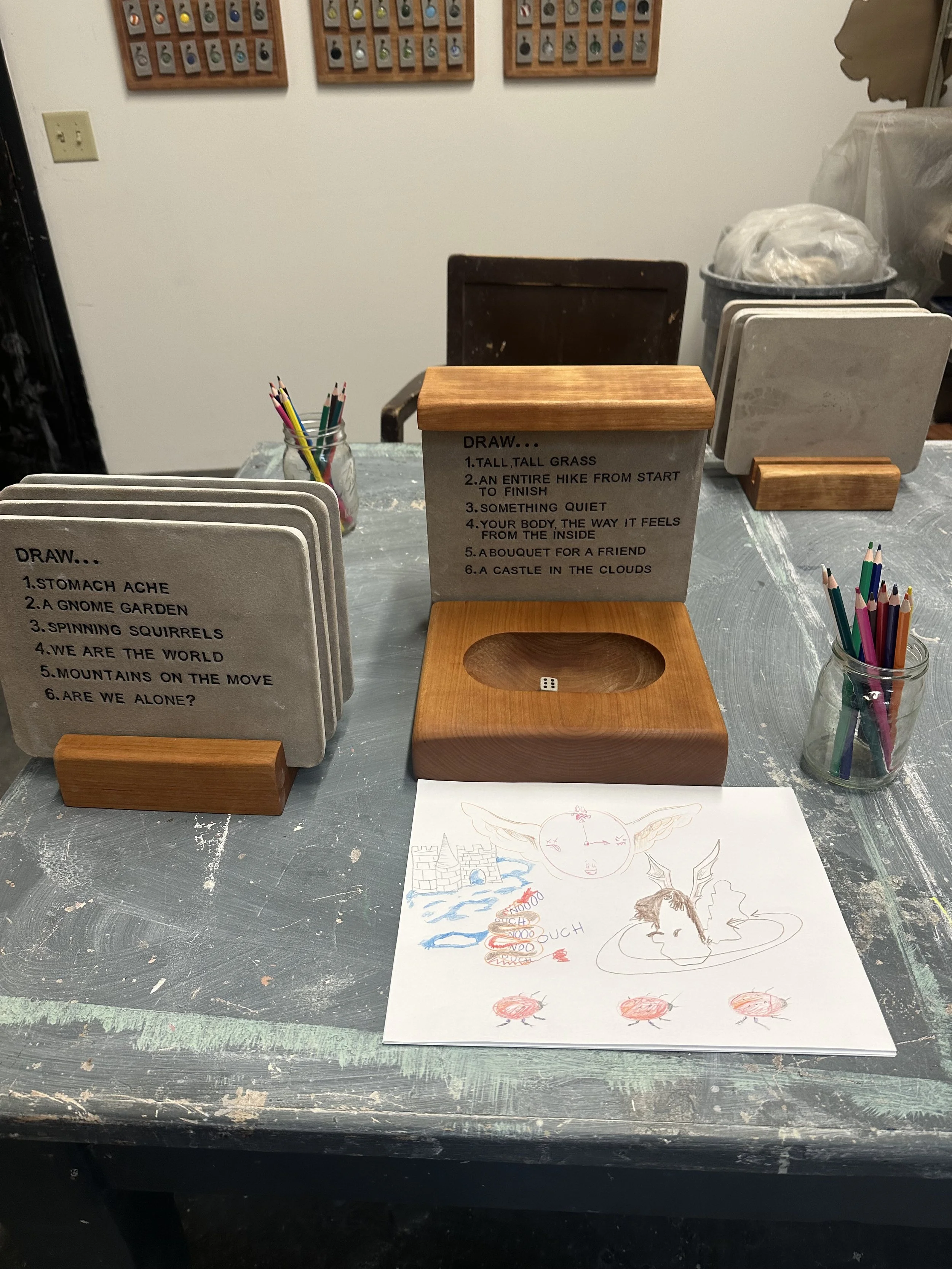

Okay, moving on to The Drawing Machine. The Drawing Machine is a different kind of interactive sculpture, its use entails two people rolling dice to determine what prompt the other will draw for 3 minutes. After 3 minutes, the players swap their drawings and roll the dice again to prompt each other to draw something else on each other’s papers. A round is complete when there are 6 drawings on each paper. In short, the function of The Drawing Machine is to make collaborative drawings.

The Drawing Machine (2025) ceramic, cherry wood, found objects, steel, magnets

In the development process of this show, the library gave me almost no directives, except for one: they requested that I make an interactive work for the Teen Deck specifically. While working on The Drawing Machine, I was thinking a lot about the relationship that many teens these days might have with making images. Everyday, millions of humans prompt machines to generate images. Whether by typing into generative AI programs or by snapping a photo with our phones, we are so accustomed to machines making images for us. The Drawing Machine inverts that relationship, it’s a machine that prompts humans to generate images.

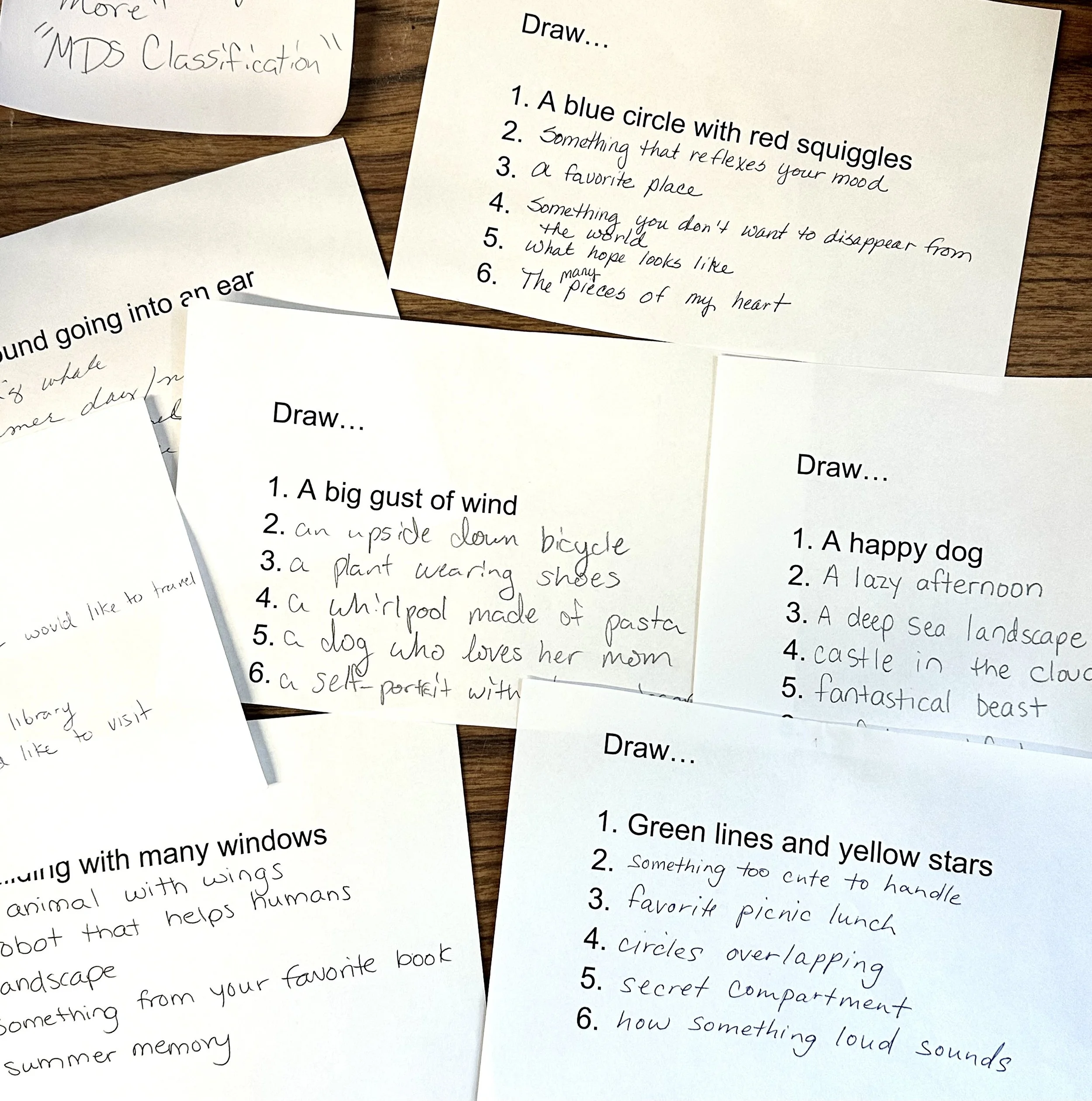

So, a bit about how this sculpture came into being. On July 1st, I sent out an email to about 80 family members, friends, and colleagues, explaining my idea for the sculpture and asking for drawing prompts.

These are screenshots of some of the responses I received.

I also took a trip to Bemis and asked librarians and staff for drawing prompts. From my database of about 200 drawing prompts, I organized them into groups of 6, trying to imagine what prompt groups might make interesting drawings. My thinking around this method of sourcing prompts from my immediate networks, was to create a kind of parallel or foil to the way that Large Language Models like ChatGPT mine our data for their content.

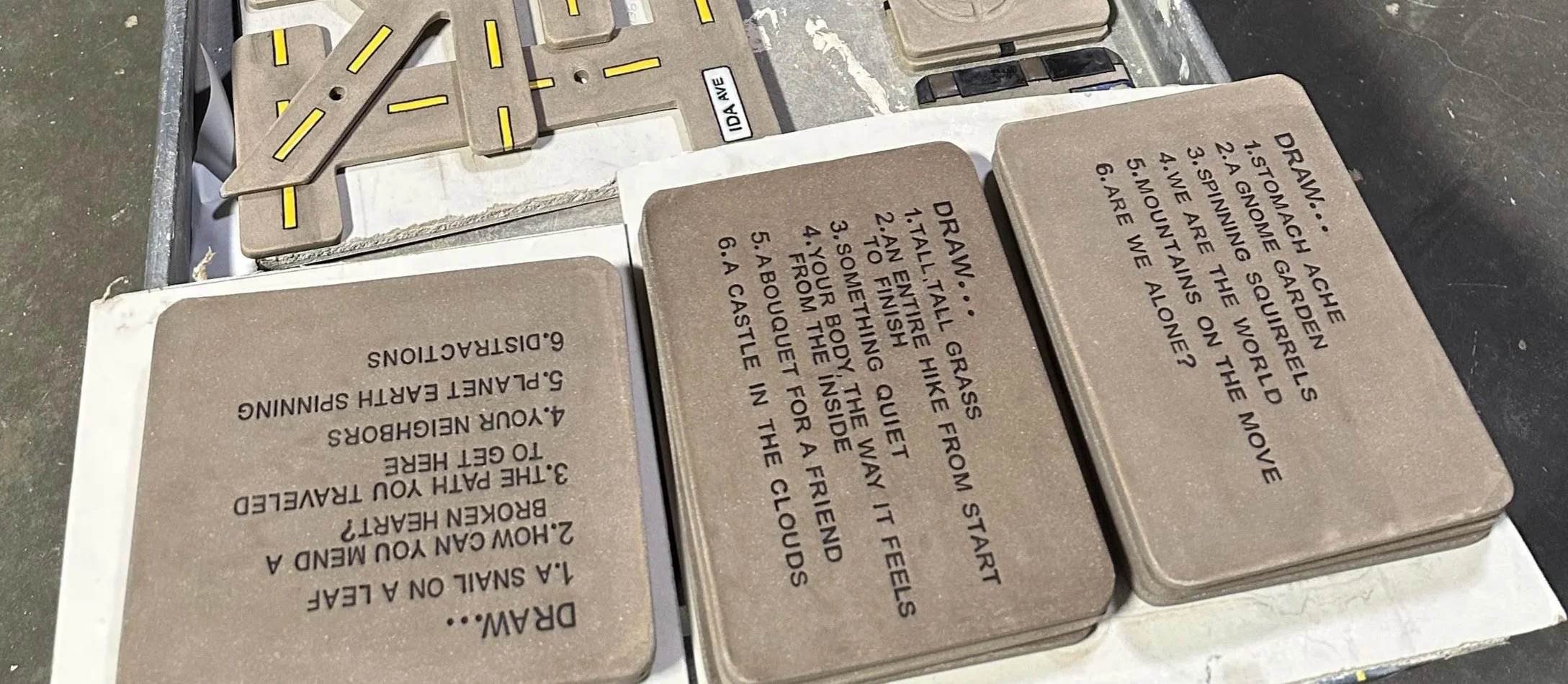

I stamped each set of drawing prompts into clay to create these ceramic “screens.”

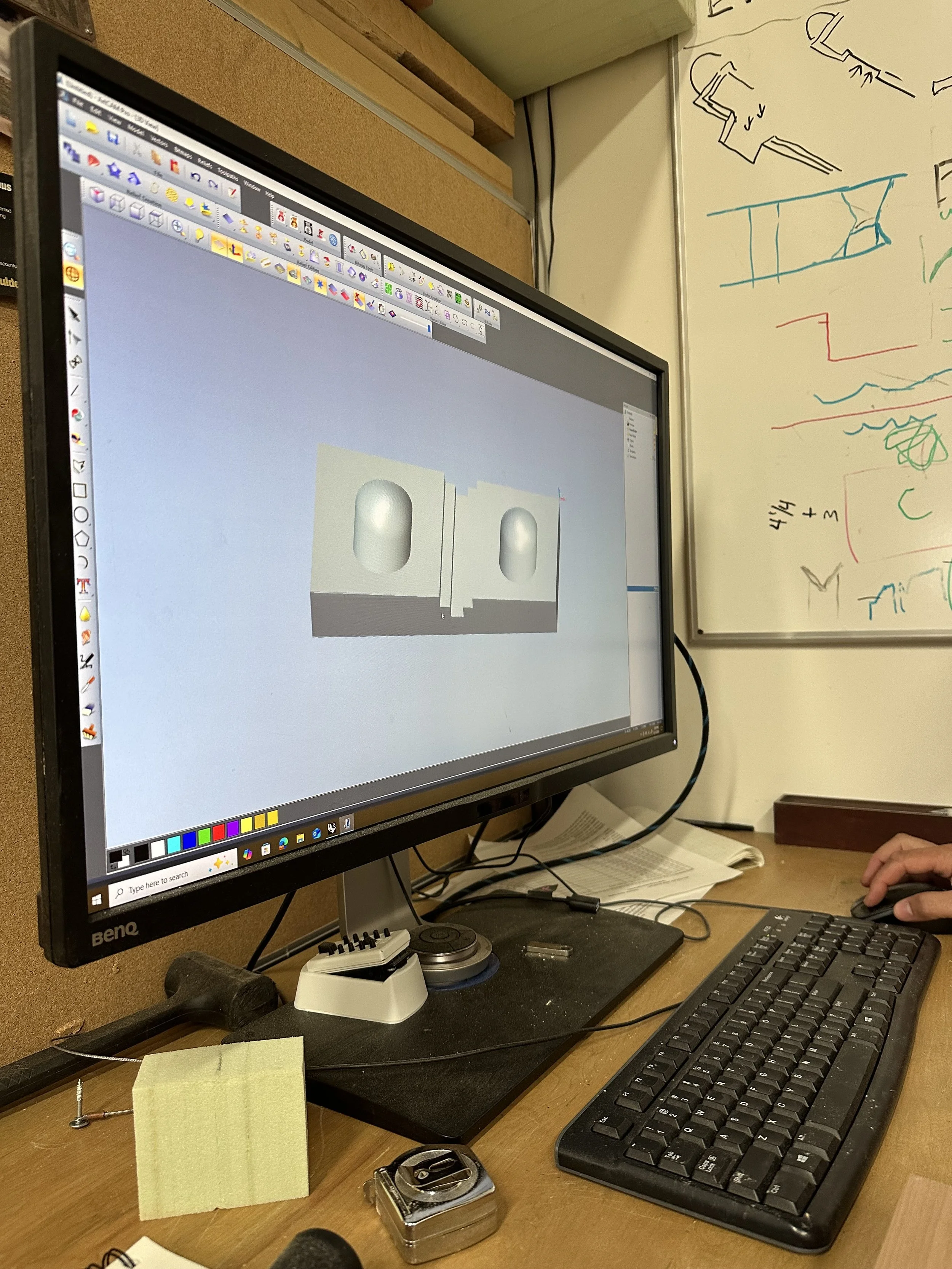

The body of the machine is cherry wood, Evan helped me cut some of the components with a computerized router.

I put all of the wooden components together, did a lot of routing and sanding and then finished the piece with danish oil.

One of the trickiest parts of making this sculpture was actually figuring out how to interact with it. And how to write directions clearly for other people. These are images of the first two times the Drawing Machine was used, by Donald Fodness and myself, and then by Cal and me.

In the couple of weeks that The Drawing Machine has been upstairs on the Teen Deck here, it’s been interesting to see how people have interacted with it. Some people seem to follow the directions and some use the machine in alternative ways, playing alone and rolling dice to give themselves prompts. I am glad that I decided to put this magnetic board up for people to hang their drawings because it provides helpful information about how the machine is being used and also allows the work to generate its own archive.

For the many people who may find drawing or art making daunting, The Drawing Machine provides people with prompts and transforms art making into a collaborative and playful activity.

Any Questions about The Drawing Machine?

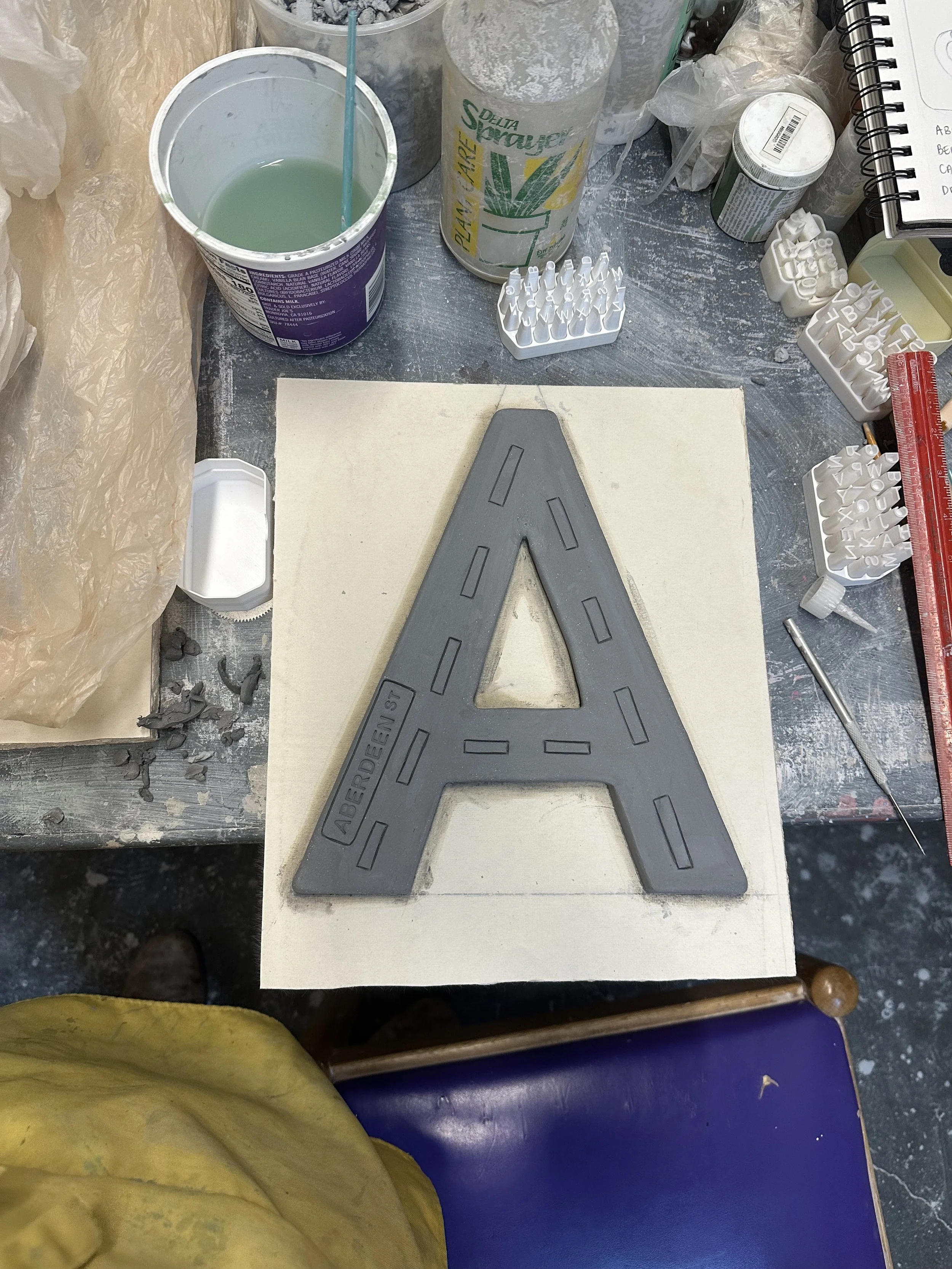

Alphabet City of Littleton (2025) ceramic, magnets

Okay, The Alphabet City of Littleton. This is the only piece in the show that does not ask for tactile interaction.

On my first site visit to Bemis in March, I saw this paper alphabet above the computer area in the Children’s Space and I knew I wanted to make a ceramic alphabet to replace it. I didn’t immediately have an idea for what the theme of this alphabet would be. I knew that I wanted it to be interesting and engaging to look at. I wanted to make something that could potentially distract the kids from their screentime.

I got the idea to make the letters look like roads after I cut out A, B, C and realized the gray clay and the curves of the letterforms already looked like roads. It definitely felt like an “AHA moment” when I decided I could name the roads after streets in Littleton.

By driving around Littleton, and also looking on Google Maps, I found street names for all but 5 letters. I was expecting I would have to think of another solution for Q, X, Y, and Z, but scouring Google, I was surprised I couldn’t find any streets that started with a T in Littleton.

For these five letters that I couldn't match to street names, I decided to put special street signs that correspond to their letters. “Quail Crossing” for Q, “Traffic Light” for T etc.

A very interesting thing happened when I was installing this work, a friendly dad came over to chat about the piece, and he said “I don’t know if I should even mention this but there is a street name that starts with a T in Littleton, it’s called Tulip Lane and its inside of a cemetery.”

Of course! Streets inside of cemeteries are not labeled on Google Maps and I didn’t think to drive around in the cemetery.

This piece of local insight was amazing and I plan to remake the T with its appropriate “Tulip Lane” street sign and perhaps even a special long black car on it as well.

By connecting the Alphabet to street names in Littleton, I hope this piece encourages not only literacy but also exploration of the local community.

Any questions about The Alphabet City of Littleton?

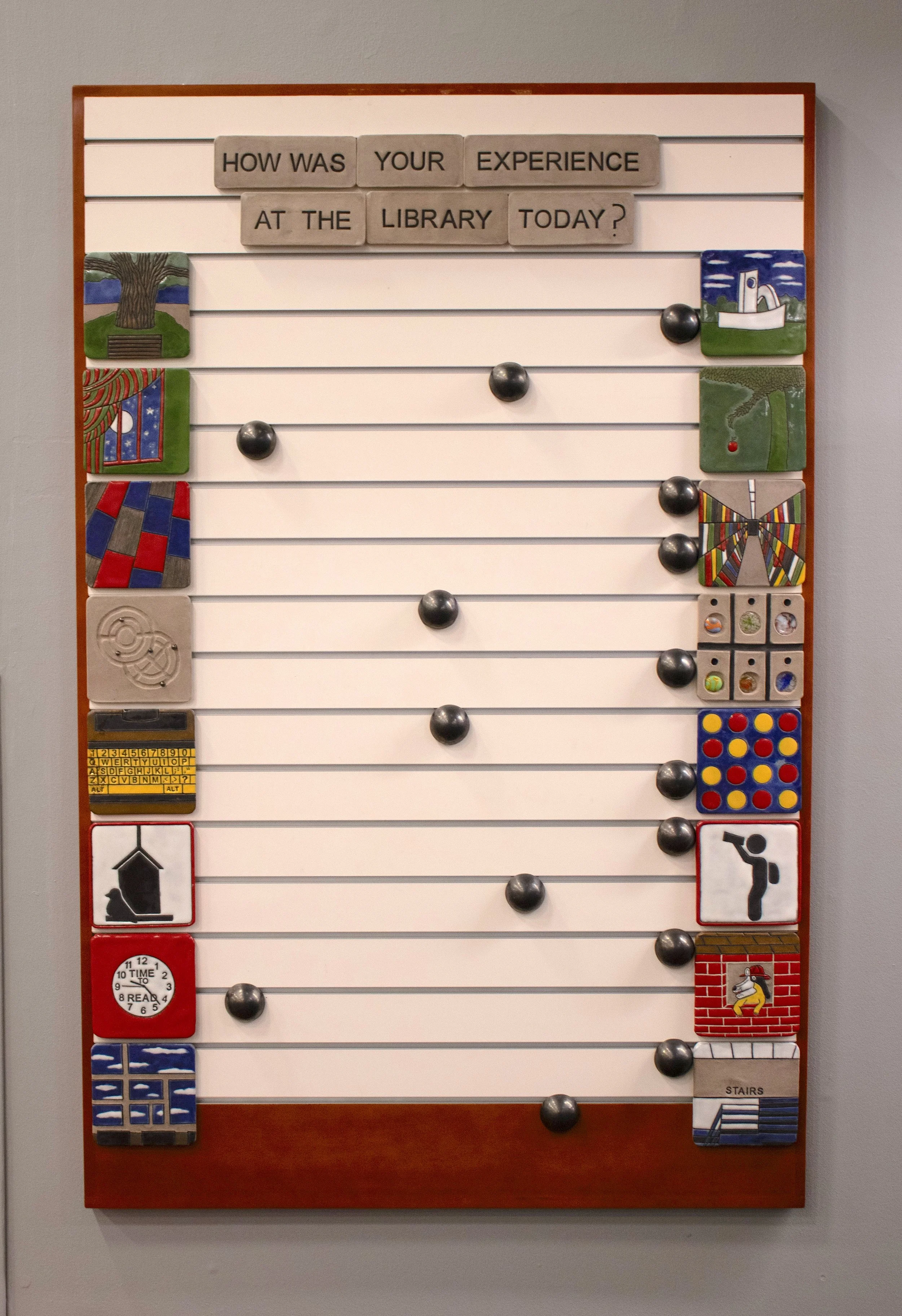

How Was Your Experience at the Library Today? (2025) ceramic, slat board inserts

Okay, How Was Your Experience at the Library Today? So this piece invites visitors to qualify their experience at the library by moving these metallic semi-spheres across this slat board between tiles that depict different images.

In April, I made a similar sculpture for the lobby area at BMoCA. The sculpture asked museum patrons to place small ceramic magnets between tiles that depicted images that ranged from mimetic representation–a distinguishable stamped image–to fully abstract representation–squiggles and indistinct shapes. This sculpture used a public survey format to encourage visitors to consider their time at BMoCA in new ways. How do you qualify an artistic experience? How is meaning co-constructed between patron and institution? How do you explain yourself without words? This theme of visual representation made sense in the context of an art museum.

For the images depicted in How Was Your Experience at the Library Today? I decided to take inspiration from the environment of the Bemis Public library. I was thinking about experience being qualified by the little details you notice around you. What you pay attention to is what determines how you experience a place. So I took lots of photos of objects and scenes that I found interesting and rendered them in ceramic.

This image is from the day I finished installing the piece. Mere minutes after I finished installing, a child, maybe 8 or 9 years old, came over to the piece and passionately slid all the semi-spheres to one side. I found this quite wonderful and funny. I think our culture is over-saturated with surveys. So often I am asked to qualify and quantify every experience I have in the world. Going to a restaurant, getting my car serviced, going grocery shopping, using an airport bathroom. I am constantly being asked to rate and review the world around me. And I wonder, where on Earth does this data go? What is the point? Sure, I guess the restaurant or the car mechanic or the bathroom might try to improve based on consumer feedback, but does this survey culture actually enrich our experiences in the world? I don’t think so. What does enrich our experiences is paying closer and deeper attention to the world around us.

Okay, any questions about How Was Your Experience at the Library Today?

The Media Archaeology Lab at Bemis Public Library (2025) objects from the Media Archaeology Lab, ceramic, found objects, magnets

Okay, finally, I would love to talk about The Media Archaeology Lab at Bemis Public Library. This is an interactive pop-up exhibit that has about 30 objects from the Media Archaeology Lab (the MAL) accompanied by various printed media, and informational ceramic plaques and objects.

The MAL was founded at CU Boulder in 2009 by Dr. Lori Emerson, and the managing director of the Lab is Dr. lili rose striegl. The MAL is home to one of the largest collections in the world of still- functioning obsolete media. It is a place for cross-disciplinary, experimental research, teaching and creative practice.

For the past year, researching at the MAL and learning about the field of Media Archaeology has been deeply influential and inspiring for my work.

The study of Media Archaeology is all about revealing the wonky, weird, and eclectic history of media. It’s about uncovering, preserving, and learning about machines, systems and networks and how they affect us. Through Media Archaeology I have learned to see that our present moment is not some inevitable consequence of “linear” progress, but rather one possibility generated out of a diverse past. It is the true diversity at the heart of the history between humans and our technologies that can provide a way forward, to reimagine our present and future relationships with technology and each other.

This picture is from the first open-hours for the pop-up here at Bemis. I love this image of kids, probably born in the last five years interacting with a typewriter from 50 years before they were born.

Before questions, I want to close by talking about the title of the show. The phrase “Books Are Machines” landed in my head this summer and it's taken me a couple of months to actually figure out how it relates to my work. At its simplest, a machine is a device with a system of parts that work together to perform a task. The machines that we use everyday require our interaction, from phones, to computers, to cars, human beings are essential participants. We are a part of the systems that make our machines work. In the same way, books don’t function without readers and art doesn’t function without viewers. This show, Books Are Machines, requires the active participation and collaborative creativity of human beings, namely all of you here today.

Thank you so much again. Any more questions before we end?